Historical Background

Ottheinrich's era is a time of upheaval. Since 1519, the Heilige Römische Reich Deutscher Nation has been under the leadership of Emperor Charles V, of Habsburg. The Reformation, triggered by Martin Luther's proclamation of the Theses, led to religious and political upheavals throughout Europe.

Important lords of the empire have already converted to the Protestant faith. In England, Henry VIII detaches the English Church from Rome, and Denmark also becomes Protestant in 1536. Calvin publishes his doctrine of predestination in this year. In Rome, the Jesuit Order was founded two years earlier as a reaction of the Catholic Church.

Charles V fights with Francis I of France over Italy, and the Turks advance several times against Hungary. Spaniards, Portuguese and French begin to settle in America. In Germany, the War of the Peasants (dt. Bauernkrieg) is only a few years in the past. In 1531, Protestant German sovereigns form the Schmalkaldic League (dt. Schmalkaldischer Bund) as a defensive alliance. The Catholic estates respond in 1538 by founding the League.

But Ottheinrich's era was also a time of discoveries, of progress in technology and science. Paracelsus, Copernicus and Sebastian Münster were still having effects. A time in which the human being as an individual moves into the foreground and, last but not least, a time of great artistic creativity. The Renaissance is in its heyday north of the Alps.

Purpose of the journey

The reason for the three-month journey, which Ottheinrich started in the fall of 1536, was the considerable financial difficulties of the Neuburg princes. Ottheinrich attempted to collect old debts on the journey. On the one hand, there are the so-called "Bohemian claims": Bohemian towns had already been pledged to the Wittelsbach dynasty by Emperor Charles IV. However, the annual annuity that had been charged as a substitute was never paid. But the Bohemian sovereign, King Ferdinand I, was not to be very amenable here either. Ottheinrich hoped to get money from his Polish relatives, since the marriage dowry of his grandmother Hedwig, daughter of the Polish King Casimir IV, had never been paid. This marriage to Duke George the Rich in 1475 is still known today as the "Landshut Wedding". Ottheinrich's efforts in Cracow are indeed crowned with success. He receives the outstanding debt of 32,000 florins from King Sigismund I of Poland in eight annual installments, but without the interest that has since accrued. In addition, the journey is supposed to finally find a rich wife for Ottheinrich's brother Philipp, after Ottheinrich's love marriage had yielded nothing materially. However, the search for a bride remains unsuccessful. Philipp finally dies unmarried. Ottheinrich's decision not to return directly to Neuburg from Krakow was apparently made on the spot, when the clash of interests between Poland on the one hand and Denmark with its allied Elector Frederick II of the Palatinate on the other intensified and Elector Joachim II of Brandenburg and also Ottheinrich stood between the parties as relatives. In this situation, Ottheinrich makes a detour via Berlin.

The reason for the three-month journey, which Ottheinrich started in the fall of 1536, was the considerable financial difficulties of the Neuburg princes. Ottheinrich attempted to collect old debts on the journey. On the one hand, there are the so-called "Bohemian claims": Bohemian towns had already been pledged to the Wittelsbach dynasty by Emperor Charles IV. However, the annual annuity that had been charged as a substitute was never paid. But the Bohemian sovereign, King Ferdinand I, was not to be very amenable here either. Ottheinrich hoped to get money from his Polish relatives, since the marriage dowry of his grandmother Hedwig, daughter of the Polish King Casimir IV, had never been paid. This marriage to Duke George the Rich in 1475 is still known today as the "Landshut Wedding". Ottheinrich's efforts in Cracow are indeed crowned with success. He receives the outstanding debt of 32,000 florins from King Sigismund I of Poland in eight annual installments, but without the interest that has since accrued. In addition, the journey is supposed to finally find a rich wife for Ottheinrich's brother Philipp, after Ottheinrich's love marriage had yielded nothing materially. However, the search for a bride remains unsuccessful. Philipp finally dies unmarried. Ottheinrich's decision not to return directly to Neuburg from Krakow was apparently made on the spot, when the clash of interests between Poland on the one hand and Denmark with its allied Elector Frederick II of the Palatinate on the other intensified and Elector Joachim II of Brandenburg and also Ottheinrich stood between the parties as relatives. In this situation, Ottheinrich makes a detour via Berlin.

Further Reading

Image source:

Further Links:

Pfalzgraf Ottheinrich

Ottheinrich of the Palatinate is thirty-four years old at the time of the journey and rules over the principality of Palatinate-Neuburg. He has been married since 1529 to Susanna, the widow of Margrave Casimir of Brandenburg-Ansbach, who brings five children with her to her second marriage. Like Ottheinrich himself, she came from the Wittelsbach family, was the sister of Dukes Wilhelm and Ludwig of Bavaria and died in 1543. Ottheinrich will be remembered by posterity as an imposing figure, and not only because of his considerable girth and sanguine temperament, which apparently characterized him from an early age. From his youthful years, a sense of power and a willingness to use violence, as well as pleasure in representation, festivities and hunting, a lack of thrift, but also tender love for his wife and great patronage have been handed down. In 1536, Ottheinrich and his brother were already heavily in debt when Philip also demanded the division of the already small principality. Finally, the principality of Palatinate-Neuburg was bankrupt, and in 1544 the entire inventory of Neuburg Castle was auctioned off. Ottheinrich has to leave his dominion, lives in Heidelberg, then in Weinheim, and finds the leisure to study the knowledge and art of his time. When he is able to return to his principality in 1552, he introduces the Reformation in Palatinate-Neuburg against the will of the Wittelsbach relatives. In 1556, Ottheinrich succeeded his uncle Frederick II as Count Palatine in Heidelberg. He turns Heidelberg and the university there into a center of Lutheranism.

Ottheinrich of the Palatinate is thirty-four years old at the time of the journey and rules over the principality of Palatinate-Neuburg. He has been married since 1529 to Susanna, the widow of Margrave Casimir of Brandenburg-Ansbach, who brings five children with her to her second marriage. Like Ottheinrich himself, she came from the Wittelsbach family, was the sister of Dukes Wilhelm and Ludwig of Bavaria and died in 1543. Ottheinrich will be remembered by posterity as an imposing figure, and not only because of his considerable girth and sanguine temperament, which apparently characterized him from an early age. From his youthful years, a sense of power and a willingness to use violence, as well as pleasure in representation, festivities and hunting, a lack of thrift, but also tender love for his wife and great patronage have been handed down. In 1536, Ottheinrich and his brother were already heavily in debt when Philip also demanded the division of the already small principality. Finally, the principality of Palatinate-Neuburg was bankrupt, and in 1544 the entire inventory of Neuburg Castle was auctioned off. Ottheinrich has to leave his dominion, lives in Heidelberg, then in Weinheim, and finds the leisure to study the knowledge and art of his time. When he is able to return to his principality in 1552, he introduces the Reformation in Palatinate-Neuburg against the will of the Wittelsbach relatives. In 1556, Ottheinrich succeeded his uncle Frederick II as Count Palatine in Heidelberg. He turns Heidelberg and the university there into a center of Lutheranism.

Further Reading

Image Source:

Further Links:

Palatine Pfalz-Neuburg

Emperor Maximilian I (r. 1486-1519) founded the small, highly fragmented principality at the end of the Landshut War of Succession (1503-1504/5) for the two sons of Elisabeth of Bavaria-Landshut (1478-1504), as compensation for the failed efforts to enforce female succession in the Landshut part-duchy. After a brilliant start, the introduction of the Reformation (1542) and an existential crisis under the Renaissance prince Ottheinrich (r. 1522-1557), the dukes consolidated the principality in the second half of the 16th century. This laid the foundation for the expansion to the Rhine: in 1614 the dukes of Palatinate-Neuburg took over the inheritance in the duchies of Jülich and Berg, and in 1685 in the Electoral Palatinate. In view of the political alignment with Bavaria, Palatinate-Neuburg had returned to the Catholic faith in 1613. At its height, the House of Palatinate-Neuburg was among the most influential in the empire, but became extinct in the male line in 1742. Karl Theodor (r. 1742-1799) from the collateral line Palatinate-Sulzbach took over the principality and also succeeded to the Electorate of Bavaria in 1777/78. Palatinate-Neuburg was since then connected with Bavarian.

Emperor Maximilian I (r. 1486-1519) founded the small, highly fragmented principality at the end of the Landshut War of Succession (1503-1504/5) for the two sons of Elisabeth of Bavaria-Landshut (1478-1504), as compensation for the failed efforts to enforce female succession in the Landshut part-duchy. After a brilliant start, the introduction of the Reformation (1542) and an existential crisis under the Renaissance prince Ottheinrich (r. 1522-1557), the dukes consolidated the principality in the second half of the 16th century. This laid the foundation for the expansion to the Rhine: in 1614 the dukes of Palatinate-Neuburg took over the inheritance in the duchies of Jülich and Berg, and in 1685 in the Electoral Palatinate. In view of the political alignment with Bavaria, Palatinate-Neuburg had returned to the Catholic faith in 1613. At its height, the House of Palatinate-Neuburg was among the most influential in the empire, but became extinct in the male line in 1742. Karl Theodor (r. 1742-1799) from the collateral line Palatinate-Sulzbach took over the principality and also succeeded to the Electorate of Bavaria in 1777/78. Palatinate-Neuburg was since then connected with Bavarian.

Further Reading

Source:

-

Markus Nadler, Pfalz-Neuburg, Herzogtum: Politische Geschichte, publiziert am 09.06.2009; in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

Image Source:

Further Links:

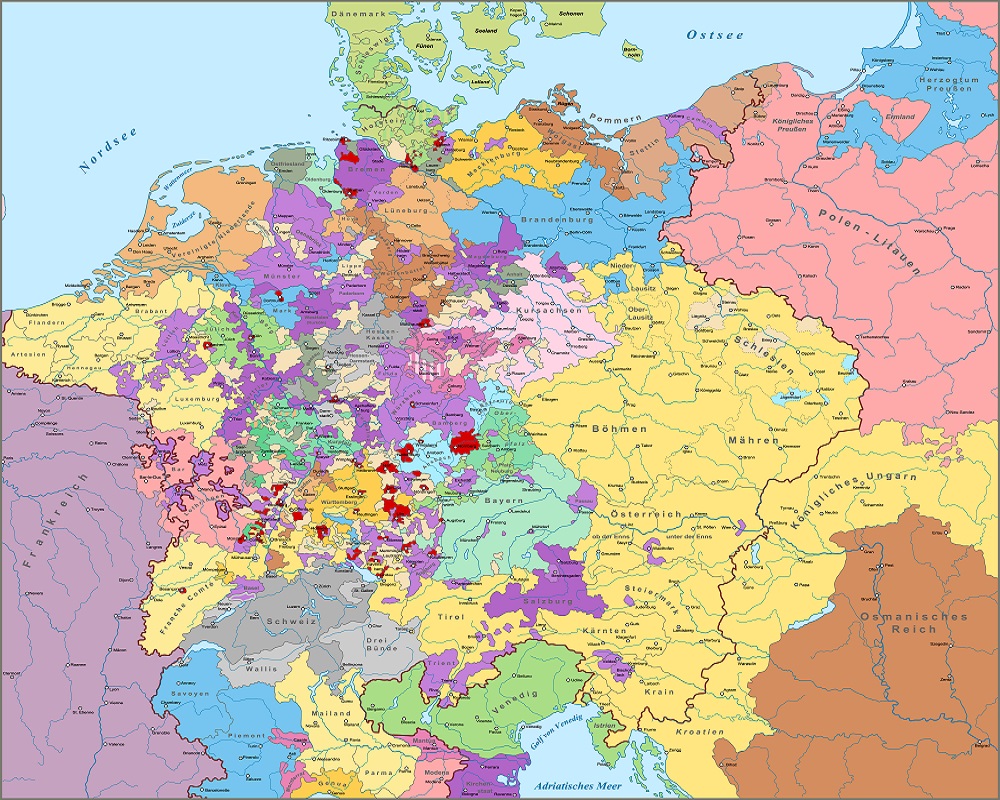

Holy Roman Empire in the 16th Century

The HRR, which existed from 962 to 1806, was a politically, legally and personally heterogeneous federation formed by secular and ecclesiastical sovereigns (individuals, corporations, monasteries) as well as imperial cities that held territories of very different sizes (including duchies, counties, manors). The common head and political center was the emperor, to whom the sovereigns had a personal relationship of allegiance. The HRR formed the framework of German history in particular, but never developed into a nation-state. The territories belonging to the HRR were inhabited by members of other nationalities who spoke Yiddish, French, Dutch, Frisian, Sorbian, Czech, Polish, Slovenian, Italian, Ladin or Rhaeto-Romanic, among others. Characteristic of the entire history of the empire was the tension ('dualism') between imperial authority and striving for central power on the one hand and the tendency toward independence of the powerful imperial estates, which ultimately acted independently of the empire and pursued their own interests, on the other. In particular, the emergence of Brandenburg-Prussia and Austria from the HRR starting in 1740 (Silesian Wars; Seven Years' War), the military defeats against Napoleon and the loss of territory to France (which led to the Imperial Deputation in 1803), and the founding of the Confederation of the Rhine (1806), which went hand in hand with the withdrawal of German states from the HRR, finally led to the resignation of the imperial crown by Franz II (1792-1806) on August 6, 1806, after he had already founded the Austrian Empire in 1804. This also formally marked the end of the HRR.

The HRR, which existed from 962 to 1806, was a politically, legally and personally heterogeneous federation formed by secular and ecclesiastical sovereigns (individuals, corporations, monasteries) as well as imperial cities that held territories of very different sizes (including duchies, counties, manors). The common head and political center was the emperor, to whom the sovereigns had a personal relationship of allegiance. The HRR formed the framework of German history in particular, but never developed into a nation-state. The territories belonging to the HRR were inhabited by members of other nationalities who spoke Yiddish, French, Dutch, Frisian, Sorbian, Czech, Polish, Slovenian, Italian, Ladin or Rhaeto-Romanic, among others. Characteristic of the entire history of the empire was the tension ('dualism') between imperial authority and striving for central power on the one hand and the tendency toward independence of the powerful imperial estates, which ultimately acted independently of the empire and pursued their own interests, on the other. In particular, the emergence of Brandenburg-Prussia and Austria from the HRR starting in 1740 (Silesian Wars; Seven Years' War), the military defeats against Napoleon and the loss of territory to France (which led to the Imperial Deputation in 1803), and the founding of the Confederation of the Rhine (1806), which went hand in hand with the withdrawal of German states from the HRR, finally led to the resignation of the imperial crown by Franz II (1792-1806) on August 6, 1806, after he had already founded the Austrian Empire in 1804. This also formally marked the end of the HRR.

Further Reading

Image Source:

Further Links: